11.01.2023

The fact that the members of the cosmonaut squad decided to obtain higher education became known almost immediately after their enrollment in the university. In fact, Yuri Alekseyevich Gagarin himself said it publicly in his short essay “Ready for new space flights” (magazine “Avia i Kosmonautika”, 1962, #4): “An urgent need for knowledge brought me and G. Titov to the auditoriums of the Military Air Engineering Academy named after Prof. N. E. Zhukovsky. In addition to excellent health, in-depth flight and engineering knowledge is necessary for the upcoming flights. A cosmonaut must be a pilot, a navigator, an engineer and a researcher.

However, Soviet publicists shared little information about the course of training, and if they did, they did so with empty phrases, behind which there was no intelligible content. They wrote in much detail about anything: the cosmonaut’s trips abroad, visits to his native land, speeches at various Party functions and meetings, meetings with pioneers, Komsomol members, workers, collective farmers, habits and preferences, family and friends – but never about what he is doing at the Academy.

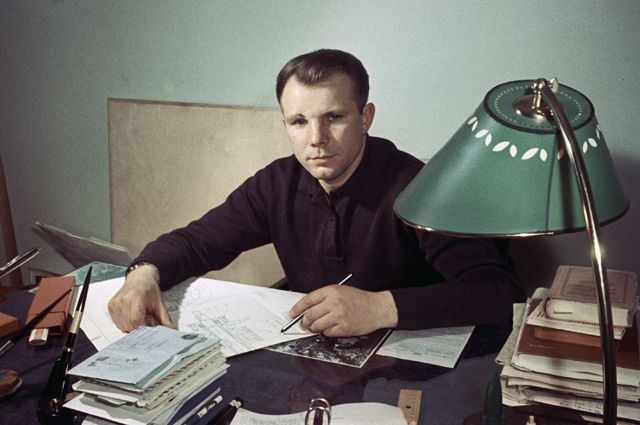

From time to time, however, photos appeared in print, showing Yuri Gagarin sitting in a classroom, looking at some drawings and diagrams, drawing something with chalk on the blackboard, working with some instruments. Because the photographs were often unsigned, an outsider had the impression that the post-flight life of the first cosmonaut really consists mainly of socio-political and educational activities, and that he is rarely in the academy, for a “tick”, being engaged not so much in science as in posing. Nothing has changed in this sense and after the death of Yuri Alekseevich. A few examples. Here is what German Titov wrote in his booklet “The first cosmonaut of the planet” (1971), published to the tenth anniversary of the historic flight: “I had occasion to many and often together with Yuri solve various flight problems, I had occasion to defend a diploma at the Academy named after LE Zhukovsky. I want to avoid hackneyed words: “I was amazed”, “I was pleased”. Let me put it this way: with Yury it was possible to do any job well and calmly and to be reliable friends”. Another place to look is the article “Pages of Gagarin’s Album” (Soviet Photo magazine, 1971, #4) by Vitaly Shitov, candidate of technical sciences: “After the space flight his life was closely connected to Military Air Academy named after N.E. Zhukovsky. Yuri Alekseyevich studied enthusiastically; he carefully, even beautifully took notes, listened attentively to the teachers’ advice, and carried out laboratory work on time. Important errands and responsibilities often took him away from his classes. Sometimes he had to leave in the middle of a lecture. But at the next class he invariably came prepared. It was unfathomable when he managed to do everything. He was helped by his ability to work selflessly, constantly and persistently. And the strictness of the teachers did not allow any indulgence in studies. ‘…’ Perhaps the most precious picture for me is a portrait of Gagarin, taken on February 15, 1968. On that day Yuri Alekseyevich was reading his thesis report. I continuously filmed it. When he finished his report, he smiled and said: “That’s it.” At that moment, I pressed the shutter. This portrait, according to his close friends and good acquaintances, shows Gagarin as he remained in their memory. On February 17, Yuri Gagarin defended his diploma brilliantly.

Took notes, went to lectures, defended his degree brilliantly – that’s all, as Gagarin would say. And this, I note, is the most detailed description of the educational process at the academy of all the published materials of the time. Other sources, even solid folios, have even less. What did the cosmonaut do within the walls of the military academy? What was the topic of his graduation work? Who were his supervisors? The mystery is shrouded in darkness.

However, a clever analyst from the CIA could probably get some idea of what exactly Gagarin and his fellow soldiers were studying. First of all, he would have paid attention to the specifics of the Military Air Engineering Academy (VVIA), whose main focus has always been the development of methods to improve combat aircraft, including by equipping them with rocket engines or rocket armament. Besides, among the photos illustrating the article “Pages of Gagarin’s Album”, he would find one very strange: it shows Gagarin, Titov, Nikolaev, Popovich and Bykovsky examining a model that resembles the Space Shuttle in its shape. Since it was at that time that American politicians, military officers and scientists were privately discussing the concept of a reusable orbital spacecraft that would take off rocket-style and land by plane, the CIA analyst would have woken up and written a memo to his superiors to the effect that the Soviets were again trying to beat the US and had even brought their first astronaut into the mix. In reality, however, the significant international resonance of this photo (only for some reason with Titov retouched) was much later, in 1989, when it was published by the newspaper Trud (January 4) as one of the illustrations to the article by Vitaly Golovachev “Preparing to fly on Buran”, which lifted the veil of secrecy on Soviet projects of reusable orbital spaceships. The appearance of the mysterious photograph in the Soviet Photo magazine did not change the situation with the availability of information about the cosmonauts’ studies at the Academy. For the first time, more or less detailed information about them appeared in the book “Gagarin’s Diploma” (1986) by Professor Sergey Mikhailovich Belotserkovsky, who headed the Aerodynamics Department at VVIA. Later an expanded version of this work was published under the title “Pioneers of the Universe. Earth-Cosmos-Earth” (1997), but we are mostly interested in the first edition, which by Soviet standards had a respectable circulation of 155,000 copies. It does not contain the mysterious photo with the Space Shuttle, but has plenty of other pictures taken by Shitov with a “hidden camera” during many years of cosmonaut training at the Academy. The main thing is that Professor Belotserkovsky described in detail how the astronauts studied, what problems they had, what sciences they had to learn, and so on. It is clear from the book that Gagarin, at the head of a group of fellow soldiers, was designing a supersonic single-seat flying machine with lattice wings. However, again there is no answer to the question what kind of apparatus it was, for what purposes it was designed, and whether it had any previous prototypes. Among the abundance of illustrative material we are obviously missing at least a general layout drawing of the craft or a full-fledged photo of it taken from a convenient angle. Again a mystery! Apparently, because of the paucity of factual information, only five pages are devoted to this remarkable episode in Victor Aleksandrovich Stepanov’s book Yuri Gagarin (1987), with a reference to Belotserkovsky’s memoirs. In the post-Soviet era, the trend has continued. Although a great deal of detail about the training of cosmonauts can be found in the published diaries of Nikolai Petrovich Kamanin, and Professor Belotserkovsky in the second edition of his book finally revealed the name of the mysterious flying machine designed by Gagarin and gave a sketch of it, biographers have ignored the topic, giving it minimal attention. One need only look at the most recent biographies of Gagarin, published for the 50th anniversary of his flight into space, to be convinced of this. Jamie Doran and Piers Bisoni in “Gagarin. The Man and the Legend” (2011) dedicated four pages to the topic, but with a fair amount of factual confusion and “bubbly cranberries” – what can you take from foreigners? Lev Danilkin in Yuri Gagarin (2011) also devoted no more than four pages to the studies of the cosmonauts, diluting the information with his speculation on the political context of what was going on. In Nikolai Yakovlevich Nadezhdin’s book “Yuri Gagarin” (2011) even half a page is devoted to a story about the VVIA (in defense of the author, one can only say that the book is not big by volume). In Valery Kupriyanov’s book “Yuri Gagarin’s Space Odyssey” (2011) the late period of Gagarin’s life is not covered at all. And so on.

There is a feeling that biographers are little interested in the thesis of the first cosmonaut. What impression is made by curious readers? Yes, that is exactly the impression that Gagarin was engaged in something boring and unintelligible, only to get the “crusts” for higher education.

However, it’s not all bad. Researchers of the history of cosmonautics Vadim Pavlovich Lukashevich and Igor Borisovich Afanasyev made a kind of breakthrough in the subject. Working on the book “Space Wings” (2009), devoted to the development of aerospace systems, they asked Aleksandr Ivanovich Zhelannikov, the head of the Aerodynamics Department of the Military Aviation Academy, for explanations and received exhaustive information on the project, on which the cosmonauts worked at the Academy. If we combine it with what is presented in Belotserkovsky’s books and Kamanin’s memoirs, it is quite possible to reconstruct this stage of Gagarin’s life, which was no less colorful and intense than any other. So, in July 1961 it was decided that the cosmonauts (both those who flew and those who did not) should get a higher education: by that time only Vladimir Komarov had it in his squadron. Together with Gagarin and Titov, Andriyan Nikolayev, Pavel Popovich, Valery Bykovsky, Alexei Leonov, Boris Valentinovich Volynov, Yevgeny Vasilievich Khrunov, Viktor Vasilievich Gorbatko, Georgy Stepanovich Shonin, Ivan Nikolaevich Anikeev, Dmitry Alexeevich Zaikin, Mars Zakirovich Rafikov, Valentin Ignatyevich Filatiev.

A year later they were joined by the girls of the women’s suite. Not all of them defended their diplomas, not all of them flew into space, but it was not because of their personal qualities, but because of the problems that inevitably arose during the preparation for the flight. The choice in favor of Zhukovsky Academy was made under the influence of the chief designer of rocket engineering Sergei Pavlovich Korolev, who had plans for this university. Of course, the curriculum began to be drawn up even before admission, and Korolyov was one of the most active participants in its discussion. One day he told Professor Belotserkovsky: “Show them how hard it is to be in our “skin”. This is very important. They felt the “skin” of the cosmonaut, but not the “skin” of the chief designer. And they need to understand well the designer’s difficulties. The problem is one, you can’t tear it apart”. Training in VVIA that formally began on September 1, 1961 was not easy for the cosmonaut, because at the same time he had to attend trainings, fly to keep his skills, do social and political work. That is why it quickly took the form of correspondence and lasted more than six years. Since the cosmonauts entered without exams and had only a mediocre secondary education, the first classes revealed serious gaps. Everyone, including Gagarin, got fines. At some point the situation became so critical that the first cosmonaut appealed to the Commander of the Air Force on behalf of his comrades-in-arms to transfer everyone to the Military Air Academy, located in Monino. It was thought to be much easier for professional officers to study there. Marshal Konstantin Andreevich Vershinin listened to Gagarin and replied, “In the near future I won’t have a flotilla of spaceships that you could command, so study there!” And the cosmonauts had to pick their brains. You have to hand it to them: in spite of the heavy schedule and strictness of the teachers, they were able to achieve great success. All the subsequent “excellent” grades, starting from the second year, the cosmonauts had solid and well-deserved grades. In his book of memoirs Belotserkovsky says that Gagarin got straight A’s before the others, which is understandable: he was always persistent in his studies and was used to catching new things on the fly.

It is interesting that in the second year of study a group of teachers began to form around the cosmonauts, who saw their work with Gagarin and the others as an opportunity to participate in the great process of extraterrestrial expansion, and with great enthusiasm set about creating a teaching method that would help them master the traditional disciplines faster than the curriculum would allow and would be directly linked to practical astronautics. Thanks to them, new textbooks uniting close theoretical courses and corresponding manuals appeared. Among the professors of the Academy at that time was, for example, Georgy Pokrovsky, a bright personality who went down in history not only by his scientific but also by his popular scientific works published in youth magazines. Among other things, he was not a bad artist, often referring in his work to the theme of space, on which he had a common ground with Alexei Leonov. Professor Belotserkovsky recalled the teaching routine this way:

“I first met the cosmonauts as a teacher at the beginning of 1964 – we began to study the course in aerodynamics of flying machines. I remember how the head of the academy’s training department, A. I. Butenko brought me to Zvezdny Gorodok – then known to very few people – and introduced me to a group of cosmonaut students headed by Gagarin. For some reason, one peculiarity immediately struck my eye, so to speak, of the classroom disposition of the students, which remained in place during all the sessions. Gagarin sat at the first table and Titov at the last. One day later I asked German Stepanovich why he always sat at the last table, even though there were empty seats in front. It’s a school habit,” was the reply. – I like to see the whole class, the whole group, in front of me. Classes at that time were held both at their place, at Zvezdnyi, and at our place, at the academy: out of four or five training days a week, two were there and two or three were at our place. Naturally, everything that required the use of experimental equipment, simulators, and computing machines was conducted at the Academy. My lectures at Zvezdnyi began at 9 a.m. and I was usually taken there by the Pobeda. We left Moscow at 7-7.30 a.m., and this went on for about a year”.

In October 1965, the question arose about the subjects of theses. Belotserkovsky met with Kamanin. The Academy put forward three topics: “Orbital Reconnaissance Plane”, “Orbital Interceptor Plane” and “Spacecraft for Striking Objects on Earth”. Kamanin did not challenge the choice, but suggested thinking about an integrated theme, “Exploration of the Moon,” within which more specific areas of work could be assigned: “Scientific apparatuses for the study of the Moon”, “Manned craft for circling the Moon”, “Manned craft for landing on the surface of the Moon and returning to Earth”, and “Defense significance of the development of the Moon”. Kamanin consulted with Gagarin, but Gagarin immediately said that the group could not undertake the moon exploration topic: it was too complex in its complexity. Eventually they settled on a spaceplane – an orbital airplane, launching on a carrier rocket, and returning, gliding in the atmosphere, to any airfield. The topic was close to the Academy’s management, the cosmonauts, and even to Chief Designer Korolev, who, before the war, tried to build a rocket plane.

Even before the appearance of the cosmonauts, the VVIA was still drafting the design for a reusable, highly maneuverable winged orbital spacecraft, called “KLA” (“Space Aircraft”) in the documents. The project appeared under the impression of triumphant launches of satellites – the academy staff guessed that in the near future a man will go into orbit, so they took the creative initiative. Understandably, due to the specifics of the academy, they focused on the issues of maneuvering in the atmosphere during the descent and landing sections. It was clear to specialists that such a vehicle should be winged. However, the wings that create lifting power are difficult to protect from thermal effects at high (hypersonic) flight speeds. The way out was found in an interesting technical idea – the use of lattice wings! They were to unfold after passing the area of maximum thermal impact, at heights of 45 to 25 km, providing wide opportunities for maneuvering. In 1962, a group was formed consisting of leading specialists of the Academy, including Belotserkovsky from the Department of Aerodynamics. The results of studies on the topic, which received the unofficial designation of “Lattice-62”, were summarized in two collective reports, which were sent to all interested organizations, including the bureau of Sergei Korolev. Thus, by the time the cosmonauts started their training there was formed a team that had experience in scientific work in the field of shaping the shape of reusable spaceplanes. It is clear that it was more advantageous for Yuri Gagarin and his comrades to take a thesis topic that was well known to their academic circle, rather than the lunar projects, to which Belotserkovsky’s staff had no access.

Each of the cosmonauts received their own independent section, which was carefully coordinated with all the others so that, taken together, all the work could be considered a technical proposal for a new spacecraft project. In the course of discussing the structure of the thesis it happened by itself that a special place was given to Yuri Gagarin. It was he who distributed the graduates to their supervisors and personally discussed the topic with Sergei Korolev, who helped to define a variant of the KLA’s appearance for the project. The academy staff was in favor of the folding lattice wings, but Korolev suggested a more traditional airplane layout.

The directions chosen by the graduates also tell us a lot about the scientific and engineering preferences of the members of the cosmonaut squadron. Yuri Gagarin was responsible for the general methodology of using the “KLA” and choosing the configuration of the apparatus (aerodynamic forms, dimensions of load-bearing elements, landing methods), thus acting as an informal “chief designer”. The system of the spacecraft emergency rescue was developed by German Titov. Andriyan Nikolayev was responsible for calculating aerodynamic characteristics and thermal protection. The internal layout and calculation of weight characteristics were the responsibility of Dmitry Zaikin. The power plant was handled by Pavel Popovich, orientation systems by Evgeny Khrunov, fuel system and liquid rocket engine by Valery Bykovsky. And so on.

The final version of the spaceplane with calculated geometric parameters was approved in 1966. On the basis of Yuri Gagarin’s drawing-sketch, a wooden model was made for aerodynamic studies, which was named YUG. Further studies of the chosen scheme revealed a problem with which all designers of such vehicles face: it was not possible to ensure balancing in all (hyper-, over-, trans- and subsonic) flight sections. In the “YUG”, this was especially evident at supersonic speeds. Many years later the problem was solved by automatic control with the help of onboard electronic computers, but Yuri Gagarin had no choice but to add to his “KLA” the front horizontal tail. It is easy to guess that he used folding lattice wings as stabilizers. At the same time, however, the question of folding and releasing the lattices at the level of specific design was not studied – it was left for later. By the mid-fall of 1967 the draft of the apparatus had been “coordinated” and a critical review of what had been done began. There was one more problem – the steep prelaunch trajectory. Alexandr Andreyevich Dyachenko, a flight dynamics specialist of the Aeronautical Institute, was brought in for consultation. Having familiarized himself with the work, he asked Gagarin: “Are you going to land the plane? Or is it not necessary?” And I heard the answer: “As a last resort, I will land by parachute. As a result, a sharply negative conclusion was issued: “There is a major defect in the work: the dynamics of landing have not been studied. Landing the airplane by parachute is absurd”.

After several days of discussion it was decided to take the following steps: to modify aerodynamics of the machine, to organize studying of the landing process in order to define the optimal method of piloting, to consider installation of a small air-jet engine, which would ensure landing. Yuri Gagarin was against the latter solution, since it would have required changing the entire graduation project. So he went the other way. At the flight dynamics department he assembled a simulation simulator that included an MN-8 computer, a pilot’s chair with control elements and registering instruments, on which Gagarin personally conducted two hundred qualifying “landings”. Moreover, the “landings” were made both in ideal conditions, and taking into account the wind and the curvature of the Earth, which along with improved aerodynamics of the apparatus allowed Gagarin to justify the rejection of the additional engine. This simulator can, with good reason, be considered the first aerobatic flight simulator in our country.

Due to the fact that the cosmonauts were going to complete their training at the beginning of 1968, in the last few months before the defense, they came to the full disposal of the Academy. They lived in a cadet dormitory and worked twelve to fourteen hours a day. A small room on the third floor in aerodynamic laboratory was allocated to Yuri Gagarin where he worked during the period from January 4 to February 16 to complete his graduation work. Since it fell to him to be the “chief designer”, then the explanatory memorandum prepared by him was twice as long as that of other cosmonauts. On February 17, 1968 Yuri Alekseyevich Gagarin defended the project brilliantly and received the qualification of “space pilot” and a diploma with honors. The depth of material knowledge and maturity of Gagarin as a research engineer is testified by the preserved tape recording of his report, read at the defense in Star City: “The aerodynamic scheme of the aircraft was selected and its aerodynamic characteristics were studied. First of all, the static characteristics of this apparatus were calculated. In the adopted methodology, the flying apparatus is replaced by a wing of a complex shape in the plan, which in turn is replaced by a vortex surface. It represents a certain number of oblique horseshoe-shaped vortices. The boundary conditions are satisfied at the calculated points.

Then by Zhukovsky’s theorem “in a small way” the distributed load acting on the wing is found. Then the total characteristics are determined. The results of the theoretical calculations, which were carried out on a BESM-2M computer, are shown in two graphs. As an example, the dependences of the lifting force and momentum on the angle of attack are plotted. ‘…’ Experimental studies were then carried out on the model of this aircraft in order to determine the same static characteristics. The experiments were carried out in a wind tunnel. From the consideration of the graphs, it follows that over the entire flight range of angles of attack, the theoretical and experimental data coincide completely and very well. Consequently, the calculation method was chosen correctly. The obtained characteristics for the layout selected after a number of trials provide the necessary general properties of the aircraft. However, in order to evaluate the dynamics of the aircraft landing and its flight properties, it is not enough to know only the static characteristics of the aircraft. They were found theoretically, using a method approximately similar to the one I have already described. The calculations were also performed on an electronic computer. As an example, the data for the damping moment by angular velocity and by the change in the position of the center of gravity are given here. ‘…’ After that, the dynamic stability of the aircraft was investigated on a special electronic simulator. Some of the results are shown in the oscillograms. These show that a vertical gust with an intensity of up to ten meters per second causes a noticeable change in the angle of attack. But then the apparatus quickly comes to the initial position according to the aperiodic law. Horizontal wind gusts of up to fifteen meters per second have also been studied. Their impact is also significant, but then the vehicle recovers its original speed. A combination of design and piloting experiments is very important for evaluating the landing and flight characteristics of the vehicle. The work pays a lot of attention to this issue. For this purpose, both in design and at the stage of preparation for flights, it is advisable to create simulators”.

Following the results of the defense, the State Examination Commission recommended Yuri Gagarin to continue his studies in the Academy’s correspondence course. He became the first cosmonaut at the Academy and the topic of his diploma was to become the topic of his master’s thesis. Another long-time dream of Yuri Alekseyevich came true: he received a higher engineering education with the prospect of rising to the rank of candidate and, perhaps, doctor of technical sciences. Unfortunately, all these plans were ruined by his sudden death. As for the mysterious “shuttle”, which photo first appeared in the Soviet Photo magazine in 1971, the investigation showed that it was a training model of a hypothetical hypersonic aircraft or cruise missile with a very long fuselage extension – just the author of the photo Vitaly Shitov (most likely unintentionally, because we are talking about the 1960s) managed to find such a foreshortening so that the cruise missile had the characteristic features of a reusable orbital spacecraft of the Buran type, The author of the photo, Vitaly Shitov (most likely unintentionally, since this is the 1960s) was able to find an angle that made the cruise missile look like a Buran-type reusable orbital spaceship. It was an accident, but very symbolic.